St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne

Carrie Lethborg, Fay Halatanu, Sonia Posenelli, Michelle Gallagher Winters

NOTE: Click here to download this article as a printable PDF.

Dr Lethborg is the Manager of Inclusive Health Action Research for St Vincent’s Health Australia and Grade 4 – Senior Social Worker at St Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne. Ms Halatanu is an Aboriginal Hospital Liaison at St Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne, Ms Posenelli is the former Chief Social Worker, Social Work Department, St Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne and Ms Gallagher Winters is a Gunditijmara Aboriginal woman from Victoria.

The authors would like to acknowledge the organisations who participated in the Advisory Committee for this study whose guidance and support was invaluable; Access Service for Koories (ASK), CoHealth Melbourne, Onemda VicHealth Koori Health Unit, Cancer Council of Victoria – Aboriginal Support Service, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre – Social Work Department.

Funding: AKoolin Balit grant funded this study, the authors are grateful to the Department of Health & Human Services Victoria for this support.

Abstract

Previous research reveals that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer manage their illness experience with a challenging number of complex psychosocial issues. A person-centred, evidence-based, culturally relevant Model of Care (MoC) was developed in response.

Methods:Translational research methods were used to trial the MoC for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer attending St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne (SVHM) during the study period. All agreed to participate (n=13). An existing needs assessment tool (Garvey et al, 2012) was used and interventions developed in response. Data mining process undertaken 3 months after to identify interventions offered. Findings: All participants were burdened with a range of psychosocial challenges. Interventions included holistic health responses, material aid, advocacy, cultural acknowledgement, community referrals and family support. Conclusion:The complex needs of this population requires a ‘whole of organisation’ response and a willingness to provide patient-centeredrather than standardised care.

Length of abstract:148 words

Implications:

- Aboriginal people living with cancer manage highly complex needs but also embody a range of strengths due to their links with community, family and culture.

- Responding to these needs requires a ‘whole of organisation’ response and a willingness to provide patient centered19rather than standardized care.

- Findings highlight the need for a specific, focused and culturally responsive approach that is evidence based and directed by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community itself.

Length of implications:73 words

Key Words:

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

Cancer

Cultural safety

Patient-centred care

There are currently around 37,991 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in Victoria, 6.9% of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population in Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2011). Compared to this population living in other parts of Australia, the Victorian numbers report the highest rates of recent illness (53.4%), chronic illness (46.3%) and cigarette smoking (57.1%)(Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2013).

Nationally, cancer is the third leading cause of death for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people after cardiovascular disease (including heart disease and stroke) and external causes (including transport accidents, and self-harm) (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2010). However, it is difficult to estimate specific incidence rates of cancer in this population and we know that the numbers available like that of most health issues for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, are an underestimation.

The estimate we do have is that the incidence of cancer for this group is probably slightly lower or close to that of the overall Australian population, but disturbingly mortality rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer are higher than the rest of the country (Australian Bureau of Statistics, AIHW, 2008, Cunningham et al, 2008). Indeed, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are more likely than other Australians to be diagnosed with advanced stage cancer and are less likely to receive adequate treatment or be hospitalised for cancer (Arabena et al, 2008).

Cancer outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders cannot be understood away from the context of social disadvantage. Indeed, this population remains the most disadvantaged of all Australians (Australian Report to the Human Rights Commission, 1998). As a group, they are underprivileged relative to other Australians with respect to a number of socioeconomic factors, and these inequities place them at greater risk of ill health and reduced wellbeing (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1999).

Two thirds (77%) of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006), as compared to 59% of the total population, report that they experienced one or more significant stressors in the previous 12 months and this population are twice as likely as their non-Aboriginal counterparts to feel high or very high levels of psychological distress (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are almost twice as likely to be hospitalised for mental and behavioural disorders as other Australians (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010).

Along with social stressors, general health status for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is also significantly lower than that of other Australians. Indeed, the health disadvantage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people begins early in life and continues throughout the life cycle. A person diagnosed with cancer in this population will most likely also be managing chronic illness; financial and/or social stress themselves, within their family or both.

Two-way education strategies are important, whereby health care personnel improve their understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ view of cancer and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people learn more about prevention and treatment of cancer from a biomedical perspective(McGrath, 2006).

St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne (SVHM) is the largest metropolitan provider of acute, adult Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander healthcare in Victoria Australia. The numbers of this patient group being cared for with cancer at SVHM is small (albeit growing). Concerns continue in relation to unequal outcomes in cancer diagnoses for this group when compared to their non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander counterparts (McGrath et al, 2006; Cancer Australia, 2015).

Foundation Study – Understanding the factors influencing the experience of cancer for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer at SVHM

In an effort to better understand the experience of those Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients with cancer cared for at SVHM, 21 medical records of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients identified as having a diagnosis and receiving treatment for cancer over the previous 24 months were reviewed. The review was conducted with approval from the SVHM Human Research Ethics Committee and using the social determinants of health model. Findings were analysed with input from Aboriginal Hospital Liaison Officers (co-authors) to ensure that a full understanding of the data had been obtained and cultural awareness was incorporated into the findings.

Some of the more pertinent findings in this study were that 49% were diagnosed with a ‘lifestyle’ cancer (24% gastro/colorectal, 10% ear nose and throat, 14% lung), allhad advanced disease at diagnosis, and 75%had confirmed metastatic disease. The majority of this cohort had also experienced challenging psychosocial circumstances that represented a significant burden in additional to living with advanced cancer, for example;

- Issues with finances (75%)

- Issues with housing (50%)

- History of family violence (63%)

- Difficulties in accessing health services (88%)

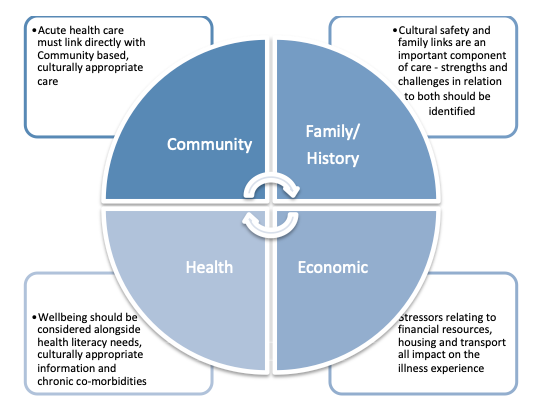

In response to these findings, a Model of Care (MoC) was developed to represent the range of responses required for the care of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer illustrated in Figure 1:

Figure 1. Components of Model of Care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer

Translation study – Operationalising the Model of Care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer into practice

Translational research methods (Sung et al, 2003) were used in the second study to operationalise the MoC into practice in relation to the setting of acute health with the following objectives:

- To operationalise the MoC to offer an early, individualised response to factors that may increase the burden of the cancer experience.

- To implement the MoC for all new Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cancer patients presenting to SVHM over a 6-month period.

- To identify complexity of factors and interventions required to implement the MoC in the acute setting.

- To strengthen and further develop partnerships with Aboriginal community organisations and to increase the inclusion of community links as part of standard cancer care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people being cared for at SVHM.

Methods

Procedures

- An Advisory Committee was established including participants from local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community controlled health services and programs, Aboriginal Hospital Liaison Officers (AHLOs), SVHM Cancer Services, SVHM Social Work and consumer representation prior to the project beginning. This Advisory Committee worked together to achieve stakeholder agreement through culturally respectful consultation in relation to:

- Study design & ethics

- Operationalised Model of Care

- Translation of results

In addition, appropriate guidelines for Indigenous studies/research were used (Cancer Australia, 2015).

- Responses and resources for each factor identified as important in the foundation study were developed including targeted and appropriately written information, identification of family, community and cancer specific supports and services.

- Additional processes of identification of new Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cancer patients attending SVHM were developed using both patient records and close communication with AHLO staff to encourage early referrals.

- A validated measurement tool was chosen to provide a comprehensive assessment of strengths and needs, implemented within one week of identification of each new participant and an individualised response provided.

- A data mining (Epstein & Blumenfield, 2004) extraction tool was developed (strongly influenced by Dwyer et al’s (2011) chronological mapping model) to guide data collection from medical recordsthat included:

- History/background information

- Diagnosis / referral; trips to service(s)

- Pre-admission; in-hospital

- Discharge/transfer

- Trips home

- Follow-up

Within these headings, data was described in relation to:

- Thepatient journey

- Family/carer journey

- Patient priorities & concerns

- Health care priorities & concerns

- Service gaps and responses

Data was entered onto spreadsheets for analysis.

In addition, a complexity scale (out of 14) was developed and used for each participant based on the following categories; with one point for each relevant factor collected for each participant:

‘Social Determinants of Health’ (9 points):

- Housing stability/security

- Health literacy

- Income issues

- Transport issues

- Access to traditional lands

- Family conflict

- Contact with criminal justice system

- Tobacco use

- Substance use

‘Intensity of Illness Experience’ (4 points):

- Experienced discrimination in health care

- Access to health care

- Advanced disease

- Many/complex symptoms

Chose SVHM for cultural safety, not the closest health service (1 point)

- Ethical approval was gained from the SVHM Human Research Ethics Committee.

Eligibility

All new Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people presenting to SVHM for cancer services over a 6-month period were eligible to participate.

Analysis

Medical records were reviewed for each participant, 3 months after their initial assessment and consent using the data mining extraction tool. Data was placed under headings for the complexity scale as a guide for data collection and information about stressors, strengths and services were described. A complexity score was also collated for each participant based on the following scoring model:

- A score of 1-5, ‘low complexity’,

- A score of 6 – 10, ‘medium complexity’

- A score of 11 or above, ‘high complexity’

This score enabled both an overall range of complexity to be identified as well as guiding interventions and resources.

Intervention

Assessment tool

Identifying the specific needs and areas of concern for each participant required a discussion tool to guide the health care professional. Alongside the MoC the key concepts of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cancer Framework (Cancer Australia, 2015) were incorporated as well as ‘Determinants of Health’, ‘Intensity of the illness experience’ and participant’s ‘Strengths’.

Fortunately, a toolincorporating all these factors (the Supportive Care Needs Assessment Tool for Indigenous People (SCNAT-IP))with cancer (Garvey et al, 2012) had previously been developed through extensive consultation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, for unmet needs research with this population and permission was given by the authors to use it for the assessment/discussion phase in this study. The tool was used toguide a comprehensive discussion with participants to identify their demographic details, challenges relating to social determinants of health, the complexity of their Illness and their individual strengths. Note that the questions from the SCNAT-IP were not asked in a formal manner but were incorporated in the early phase of the therapeutic relationship between the AHLO, the social worker and the participant.

Response

Individualised responses to each assessment were developed by the AHLO and/or cancer social worker in consultation with each participant. The aim of this intervention was to address unique needs rather than to offer standard services. The staff involved were encouraged to focus on ‘whatever it takes’ to attempt to meet these needs.

Results

Advisory Committee

Consultation occurred with a committee made up of the Onemda VicHealth Koori Health Unit, the Access Service for Koories (ASK), coHealth Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Program, the SVHM AHLO Program, SVHM Social Work, SVHM Cancer Services and the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre. Preliminary discussions were also held with the Aboriginal Program at the Cancer Council Victoria.

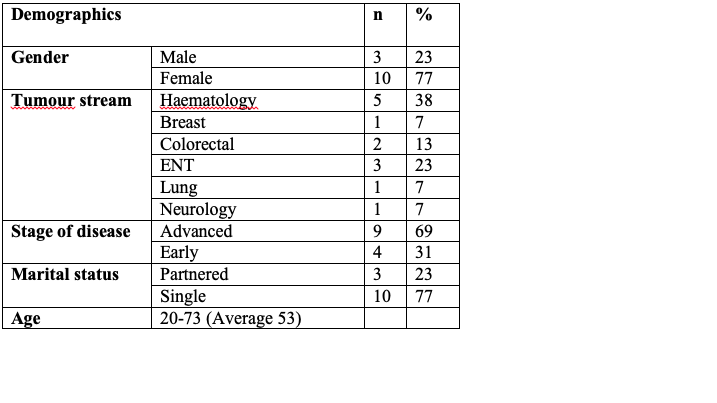

Eligible individuals during the six-month study period (n=13) were identified on admission. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identification is a mandatory requirement for hospital admissions (AIHW Best Practice Guidelines, 2013), and all agreed to participate in this study. Most of this cohort were female (77%), had advanced disease (69%) and were single (77%). The cohort had an age range of 20 – 73 years with an average age of 53 years. All participants identified as Aboriginal (thus no Torres Strait Islander people were involved in the study). Almost half of participants (46%) had cancers that are often caused by lifestyle choices (See Table 1).

Table 1. Participant demographics and diagnostic information

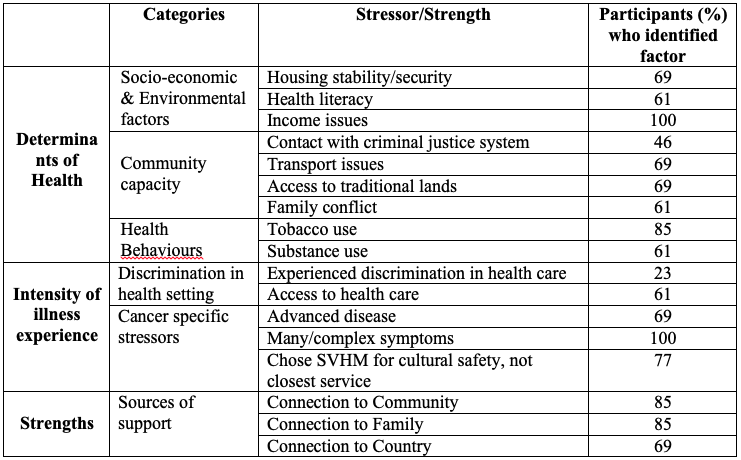

The number of participants that identified each factor as pertinent to their experience is described by percentage in Table 2 with an aggregated percentage included by category.

Table 2. Stresses and Strengths identified by Participants

Assessment

Participantsreceived support from the AHLO and/or the cancer social workers within 48 hours of their contact with the hospital (40% on the first day of admission). Based on the data collected 6 months after their initial assessment, participants had an average complexity score of 9 (5-12) with over half (52%) resulting in a score of ‘high complexity’.

Interventions

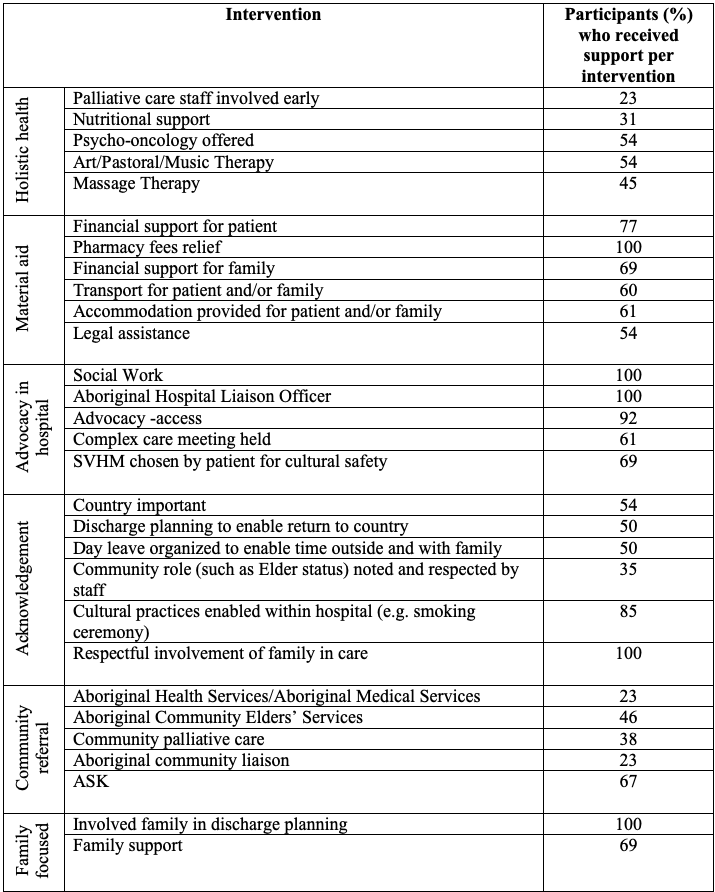

Given the range of factors identified, interventions were appropriately varied and comprehensive as illustrated in Table 3. All participants received some level of practical/material aid and advocacy while they were in hospital, referral to a community-based service and acknowledgement of family was also centrally important.

Table 3. Interventions provided under the Model of Care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with Cancer – SVHM

In addition to the number of services received by each participant, an average of 6 different staff members (aside from medical and nursing staff) were involved with their care (a total of 78 staff across the cohort) and 85% benefitted from a complex care meeting of experts to ensure the highest possible chance of a successful, appropriate discharge.

Discussion

Drawing on evidence based approaches and a culturally responsive continuous improvement framework(Renhard, 2010), the authors worked closely with Aboriginal staff and Community services to guide this study. The MoC developed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer was broad, holistic and culturally informed and offered a crucial framework. The SCNAT-IP (Garvey et al, 2012) developed with comprehensive community involvement and scientific rigour, enhanced this process. The social determinants framework proved to be an important guide for needs assessment as participants exhibited complex, distressing and broad needs over and above their cancer diagnosis.

Complexity and needs

Participants scored at the medium to highest range for complexity of need, with all experiencing challenges from social determinants of health as well as being burdened with complex and distressing physical symptoms (the majority were living with advanced disease). All participants had difficulty in relation to financial issues with many (69%) also experiencing some difficulty with housing, transport for themselves and/or family (69%) and most (84%) were managing family needs in addition to their health issues. Adding to these complexities, over half had health literacy needs and noted difficulties comprehending diagnosis and treatment planning.

Complex responses to complex needs

Given the high level of need unrelated to their cancer experience, the majority of assistance provided came under three broad categories:

Cultural Responsiveness:

- Acknowledgement of the person being Aboriginal

- Advocacy to assist with access to services such as the emergency department

- Facilitation of links to culturally appropriate community based services

- Providing family focused care

Material Aid:

- Direct financial aid

- Negotiation for reduced costs with other services

- Pharmacy fees relief

- Accommodation and/or transport costs covered for patient and/or family

Holistic focus of health:

- The provision of a broad range of supportive interventions by hospital staff

The importance of care being community based and linked to Aboriginal lead organisations was actively acknowledged. All participants’ care included discussion with their family and an acknowledgement of their role or the importance of the Aboriginal community (such as being an Elder or being involved with specific committees or organisations). Medical record notes revealed staff respectfully asking about cultural connections (including discussion about the importance of country and this being a priority in care planning) and enabling cultural ceremony (such as a smoking ceremony after someone passed away). Specific actions to smooth access such as advocacy for emergency admissions were also apparent. A total of 63 actions of support specific to cultural needs were identified in participant files.

A complex care meeting involving the participant, a member of their family (at least one), a senior social work, cancer social work, an AHLO, other staff and community members involved in the person’s care was held for 11 of the 13 participants. All participants were referred to culturally relevant community services depending on their individual needs, with a total of 26 referrals to culturally relevant community services made.No participants discharged themselves against medical advice during the study period. All participants were provided with practical support for themselves and their family including financial assistance, accommodation and transport assistance. All participants accepted the provision of fee relief from SVHM’s pharmacy.

These broad responses to the complex challenges of this group of Aboriginal people with cancer are quite remarkable. The notion of offering ‘whatever it takes’ to enable a person to access the best possible care available to them was enacted for each participant. The broad assessment process used ensured that support was entirely patient/family centred.

Data illustrates a story of compassionate, culturally responsive care where staff from across SVHM responded in detailed ways to counter the burden each participant carried. It must be also acknowledged that participants brought with them extraordinary resilience, generous trust in spite of past negative experiences with health services and the additional strength of connection to family, community and country.

Implementing the MoC into practice then, required a ‘whole of organisation’ response and a willingness to provide patient centered (Institute of Medicine Report, 2008) rather than standardized care and operationalised the principles of cultural safety (Williams,1999), highlighting the importance of:

- Respect for values, preferences and expressed needs, especially cultural needs – and the need to keep ‘checking back’ to ensure these are still being addressed throughout a program

- Partnership with Aboriginal community organisations and programs

- Early and ongoing involvement of AHLOs and social work staff in comprehensive assessment and support, to alleviate distress

- A ‘whatever it takes’ approach to planning and providing practical supports

- Involvement of family and friends

- Providing culturally appropriate information in a way that the person and their family can understand and use

- Coordination and integration of care, internally and externally and close attention to transitions/continuity of care

The majority (77%) of participants mentioned that they had chosen to receive treatment at SVHM either as their first hospital of choice for cultural safety or after starting treatment at another health service and ceasing to attend due to cultural insensitivity experienced. The following case example illustrates how the broad support offered to one participant produced extraordinary results – details of this case are purposefully left broad to ensure anonymity of the participant.

Case example

- The participant was young, from a rural area, a sole parent with a difficult to treat cancer. They had previously been unable to regularly attend treatment at two different health services due to complex family issues and lack of resources. This situation clearly put their life at risk as the participant had missed crucial anti-cancer treatment and did not feel able to continue with the regimen offered to them for practical reasons. SVHM coordinated community based supports to provide accommodation for the participant and their family, transport, financial support for petrol, childcare and living costs during treatment and worked with medical staff to gain funding for a high cost rescue treatment. Medical, AHLO, social work and community based workers came together with the participant and their family to develop a care plan that everyone was happy with and it was written up in a way that was understandable to all. At the end of this study the participant was almost through treatment, had attended every appointment and had been linked in with support from Aboriginal Elders living near SVHM.

Conclusion

This study illustrated the level of complex needs Aboriginal people living with cancer have to manage on a daily basis. These needs are multifaceted, but participants also showed a range of strengths connected to their links with their community, their family and their culture. Findings highlight the need for a specific, focused and culturally responsive MoC that is evidence based and translated into practice with direction, advise and wisdom from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community and to do ‘whatever it takes’ to provide relevant patient-centred care.

3171 words

References

Arabena, K., Wainer, Z., Hocking, A., Adams, L., Briggs, V. (2008). Rethinking Cancer, Raising Hope: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Victorian communities’ ‘state of knowledge’ on cancer roundtable: report, Melbourne: Onemda, University of Melbourne.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (1999).The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2006).National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Australia, 2004-05, Canberra: ACT.

Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2008). The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2010). Australian demographic statistics, Dec 2009, Canberra, ACT.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2011). Census of Population and Housing.Canberra, ACT.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2010). Australian hospital statistics 2008-09, Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2013). Towards better Indigenous health data. (Cat. No. IHW 93). Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2013). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2012: detailed analyses. (Cat. no. IHW 94) Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

Australian Report to the Human Rights Commission. (1998). CCPR/C/AUS/98/3 Cancer Australia. (2015). National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cancer Framework. Cancer Australia, Surry Hills, NSW.

Cunningham, J., Rumbold, A. R., Zhang, X., Condon, J.R. (2008). Incidence, aetiology, and outcomes of cancer in Indigenous peoples in Australia. Lancet Oncology. 9(6), 585-595.

Dwyer, J., Kelly, J., Willis, E., Glover, J., Mackean, T., Petarsky, B., Battersby, M. (2011). Managing Two World’s Together: City Hospital Care for Country Aboriginal People– Project Report – Flinders University, Government of South Australia, the Lowitja Institute.

Epstein, I., Blumenfield, S. (Eds.). Clinical data-mining in practice-based research: Social work in hospital settings,2004, Binghampton, N.Y. Haworth Press.

Garvey, G., Beesley. V. L., Janda, M., Green, A. C., O’Rourke, P., Valery, P. (2012). The development of a supportive care needs assessment tool for Indigenous people with cancer. Bio Med Central Cancer, 12(300).

Institute of Medicine (IOM) report. (2008). Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs, Institute of Medicine (IOM)

McGrath, P., Holewa, H., Rayner, R., Patton, M., Ogilvie, K. (2006). “Insights on Aboriginal peoples’ views of cancer in Australia”, Contemporary Nurse, 2: 240-254.

Renhard, R., Willis, J., Chong, A., Wilson, G., Clarke, A. (2010). Improving Culture of Hospitals Project: Final Report, Australian Institute of Primary Care, Latrobe University.

Sung, N.S., Crowley, W.F. Jr., Genel, M., et al. (2003). Central challenges facing the national clinical research enterprise. JAMA. 289(10): 1278-1287.

Williams, R. (1999). Cultural safety – what does it mean for our work practice? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 23(2), 213-214.

483 words